Comments Off on Fail Better

If technology will never replace perspiration, then how does one become a master of one’s craft? I mentioned briefly in an earlier post, “Living A Life of Significance,†Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers. In it, Gladwell borrows from the work of psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, who had studied how people developer expertise for many years.

Simply put, becoming a master or expert takes time and lots of it—at least 10,000 hours, to be exact. I broke down that number further:

· 3 hours a day

· 6 days a week

· 50 weeks a year

· 10 years

Now you understand why the world has more amateurs than experts in any given discipline unless of course you count sleeping, checking email, and watching television as disciplines.

Most of us don’t carve out and protect enough time. We don’t apprentice ourselves to a craft because we have many other obligations and responsibilities, everything from a “day job†to rearing children to yard work.

Though I won’t speculate about other generations, I will speculate about my own. I’ll be thirty years old in April, and if I can say one thing with confidence about Generation Y, it is this: many of us are chronically noncommittal.

Getting a “yes†or a “no†out of someone my age is like asking for an organ donation. We have more free time than perhaps any generation that has come before us, and thus we have the luxury of big dreams. Yet, we hesitate before committing to anything that will take longer than an hour or two.

Of course I’m making a generalization and building a straw man to have something to knock down, but I hope my point is clear:

Gaining the expertise necessary to do significant work takes a tremendous amount of time. This dedication acts as a deterrent. We want the food without the plow, the muscles without the exercise, the prestige without the practice.

Practice is simply failing in a particular direction, but we want success without failure.

We live in a world of bowling lanes with bumpers. When we cushion children from failure at every juncture, we teach them that success is a birth right. When everyone gets a superlative, superlatives lose their meaning, and Samuel Beckett’s words from Worstward Ho read like an antique primer:

“All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.â€

If I could teach my children—were my wife and I to be blessed with any—anything about doing significant work and pursuing one’s passion, then I would teach them that simple phrase, “Fail better.â€

How many layups and jump shots did Michael Jordan miss? How much money has British billionaire Richard Branson lost of the course of his career? How many songs did The Beatles write and never record? How many pages of how many words did Jane Austen write and throw away?

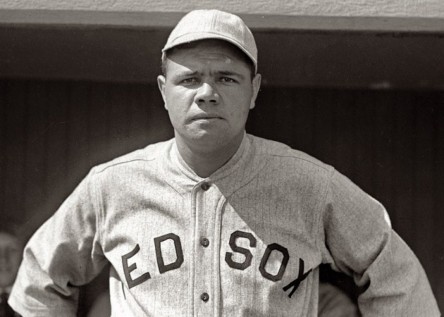

Babe Ruth hit 714 home runs. He struck out 1,330 times. If you swing for the fences, you always run the risk of embarrassing yourself.

Babe Ruth hit 714 home runs. He struck out 1,330 times. If you swing for the fences, you always run the risk of embarrassing yourself.

It’s hard to be cool and fail better at the same time. The cult of convenience will keep many of us from developing a stockpile of patience and diligence, and the cult of cool will keep many of us from failing fast and often enough to succeed.

Now, whenever someone shares a dream or a goal with me, I find myself passing on a piece of advice that is at once ancient and ultra-modern:

Dedicate your time to learning how to fail better.