I haven’t posted on gu.e since early December. Though I don’t feel the need to defend myself, I would like to inform my faithful readers—all three of you—that I haven’t forgotten about the blog or stopped writing.

About a week before Christmas I crunched some numbers and discovered that to meet my goal for the year—two posts on average per week—I would need to write a post every day for the rest of December. More and more days slipped by, as they tend to do during the holidays, and the day after Christmas, I found that the number had doubled: I would need to write two blogs posts every day to meet my goal.

My goal went unmet.

This is first a confession and second, an introduction.

I pledged to write 104 blog posts in 2011, and though no one will be taking me to court or demanding satisfaction, I want to come clean: I failed to meet my goal. A couple of dozen first drafts are waiting on my hard drive. I could have met the goal without producing any new work, but I made the choice to spend that time with my family instead.

I have tried to set a good example in the way of setting, publicizing, and meeting goals, but I am a mere mortal after all.

As to the introduction, I have decided to take a hiatus from gu.e to pursue two other creative projects. The first is a novel. I have been chipping away at a stupidly ambitious, Tolkienesque high fantasy affair that will probably take me ten years and several gallons of blood to write.

I committed the first two chapters to paper last June, and in the months since, the many characters and places and themes and Near Eastern mythologies in orbit around the main character have taken on too much gravity. I can’t ignore them anymore. For better or worse, I have to finish a first draft. Maybe then I will enjoy some peace and quiet, though I doubt it.

I have also embarked on another adventure that is part creative hijinks, part entrepreneurship.

This quote from Steve Jobs about his colleagues in the early seventies has helped me understand why I had to do it:

“The best people in computers would have normally been poets and writers and musicians….They went into computers because it was so compelling. It was fresh and new. It was a new medium of expression for their creative talents.â€

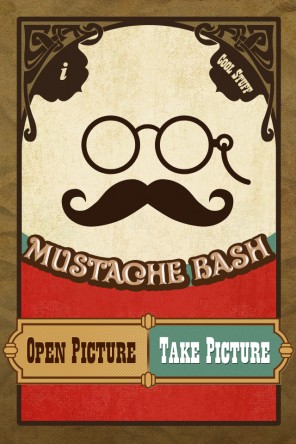

I created a mustache app for iPhone called Mustache Bash (http://www.mustachebashapp.com). The core functionality of the app is simple: the user takes a picture or selects one from the camera roll and then adds a mustache or beard to it from a gallery of mustaches and beards. Some of the bells and whistles include being able to tap the mustache to change its color and share it with other people via Facebook, Twitter, or email.

For those early adopting app-ivores out there who might be thinking, “Wait, haven’t I already seen several apps like that?†I have an answer: You’ve already seen several apps like that.

Mustache Bash is not a novel idea. I didn’t set out to create something new but to bring a better option to an existing audience. My designer’s work up to this point gives me confidence that my app will be the belle of the ball. Thankfully, the design of the other apps made that part easy.

Mustache Bash is not a novel idea. I didn’t set out to create something new but to bring a better option to an existing audience. My designer’s work up to this point gives me confidence that my app will be the belle of the ball. Thankfully, the design of the other apps made that part easy.

Many of the other apps have a tendency to crash and have either too few features or too many. I have spent several hours reading reviews of the other mustache apps and identifying their users’ major frustrations with them, and my developer has helped me refine the concept and to spend time and money implementing only those features that people will use.

Steve Jobs became famous for saying something along the lines of, “You have to give people what they want before they know that they want it.†The inverse is also true, especially with apps: Don’t give people what they don’t want.

The iPod had plenty of competition, and the way it beat out other mp3 players was by stripping away, not adding, superfluous features. The iPod makes it easy to organize and play music, and more importantly, to buy more. The genius of the iPod wasn’t what it did. The genius of the iPod was its seamless integration with iTunes—and thus, with the millions of credit cards that Apple has on file.

I wrote about Thomas Edison quite a bit last year, but I don’t think I shared his most important discovery. He had made several improvements and upgrades to the run-of-the-mill telegraph that people around the country were using and successfully developed a better telegraph.

He ran into a problem: nobody wanted to pay for a better telegraph.

From that point forward, Edison vowed to focus on inventions that he could bring to market, and history—at least the way history is told in textbooks—vouches for this discovery: the people who receive credit for inventions aren’t the first ones to have the idea but often the ones who were able to make the idea popular enough to spread and cheap enough to sell.

Mustache Bash is ridiculous, yes, but there’s just something funny about putting a mustache on a picture. It seems perfectly in keeping with everything gu.e has come to represent. Bristly moles and unibrows will be even better, but I’ll save those facial embellishments for future apps.

Mobile application development isn’t the same as good writing and storytelling, but Mustache Bash is one of the next chapters my own story will tell.

It is alive and well in the App Store. Download it here: http://bit.ly/MustacheBashapp.

Thanks to everyone who has taken the time to read one of my posts. I’ll still make the occasional post here, and I’ll send out regular updates in my email newsletter.